Treasure Islands: May in the Dry Tortugas

We were on the top deck of the ferry headed back to Key West, watching the big fort and tiny islands fade from view, when one of the people I met during three days in Dry Tortugas National Park summed up what we had just experienced.

We were on the top deck of the ferry headed back to Key West, watching the big fort and tiny islands fade from view, when one of the people I met during three days in Dry Tortugas National Park summed up what we had just experienced.

Mark Freund, a deeply tanned 62-year-old basket weaver, has been living in the Keys for about 30 years. His home is a sailboat near Big Pine Key. So he already had plenty of stories to tell, many of them true. But his first visit to the Dry Tortugas, a camping trip with his son Kevin timed to coincide with the fullest of full moons — a sphere so big and bright that it was being dubbed a Super Moon — left both of them in awe.

“This is the kind of trip I’ll wake up tomorrow and say, ‘Did this really happen?’” Mark Freund said.

I couldn’t help but think that human beings — from pirates to prisoners to tourists — had been saying similar things for nearly 500 years, ever since Ponce de Leon and his crew found a cluster of 11 small islands teeming with wildlife in 1513. The Spanish explorer named them “Las Islas de Tortugas” (the islands of turtles). On mariners’ charts, they eventually were labeled as “Dry” to alert those sailing the Gulf of Mexico that there wasn’t any fresh water there.

Four hundred and ninety-nine years later, the Tortugas are down to seven keys. They still are home to all kinds of wildlife. And there still isn’t any fresh water.

So I went from April in the Grand Canyon, where layers of land go a mile deep and a river perpetually quenches millions of Americans, to May in this place: a national park that includes 100 square miles of water, none of it drinkable, and less than 100 acres of dry land.

Why the Dry Tortugas?

Partly because of that wonderfully jarring juxtaposition. Partly because this is a real place that seems ripped from the pages of “Treasure Island” (Long John Silver told stories of the Dry Tortugas) and a Hemingway novel (the author and some buddies once were stranded there for 17 days). Partly because while national parks often feature natural treasures or cultural ones, this park features both: coral reefs, wildlife and one of the largest forts America ever built.

But mainly I went there because I’m trying to look into the future, to the National Park Service celebrating its centennial in 2016 and beyond. And in another 100 years, much of what led to this becoming a part of the park system in 1935 almost certainly will be dramatically different, changed by a combination of rising seas, shifting sands and dwindling budgets.

Within the park service, climate change isn’t a controversial issue. Or at least not in the way it is on the campaign trail and cable news. The question isn’t whether it’s occurring, but how it is altering parks and — perhaps an even tougher question — how the park service should react to these changes.

As part of my trip to the Dry Tortugas, I made a sidetrip to Homestead, a few miles from the entrance to Everglades National Park, to meet with a couple of NPS scientists. As two guys with Ph.D.s — Leonard Pearlstine is a landscape ecologist and Erik Stabenau is an oceanographer — tried explain to me what was happening in South Florida’s national parks, rattling off all kinds of factors affecting water or vegetation or wildlife, they’d eventually pause, smile and repeat what they had said moments earlier.

“It’s complicated.”

That’s one of the problems with so many discussions about climate change and its effects. We don’t want it to be complicated. The conversations get boiled down to a debate or poll question about whether or not you believe. Our climate is changing. But how is it changing and what should we do? That’s complicated.

To get into the topic, it was hard to decide where to go. In some way, all of the 397 NPS sites — everywhere from Alaska to the Virgin Islands — are being affected. I wanted to pick one. I thought about going to Glacier, where the glaciers are disappearing. Or to Joshua Tree, where the namesake tree is facing threats. Or to the Everglades, where it doesn’t take a PhD to know that even the slightest rise in sea level could have dramatic implications not only for the park, but for millions of people in Florida.

But when it comes to climate change, the Dry Tortugas (highest natural spot: 10 feet above sea level) might be the canary in the coal mine.

Or, to be more accurate, the 80,000 sooty terns on a coral island.

I wanted to experience more than a few hours there. I wanted to be there when the stars and, especially the moon, came out. So I camped, just outside the walls of a fort that represents one of this country’s most remarkable logistical accomplishments.

One hundred years before we sent a man to the moon, we took 16 million bricks to a small island in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico.

Thanks to Mike Jester for showing me around the place, for explaining the challenge of figuring out what to do with it in the future. (Suffice it to say, it’s very complicated. And expensive. So much so that when I met with NPS director Jonathan Jarvis in Washington last fall he raised the ultimate question for the future of the fort: “When do you let it go?”) And thanks to Wayne and Kathy Landrum and others for sharing their experiences. I’ll save most of the stories for later, for whatever this project eventually becomes.

Thanks to Mike Jester for showing me around the place, for explaining the challenge of figuring out what to do with it in the future. (Suffice it to say, it’s very complicated. And expensive. So much so that when I met with NPS director Jonathan Jarvis in Washington last fall he raised the ultimate question for the future of the fort: “When do you let it go?”) And thanks to Wayne and Kathy Landrum and others for sharing their experiences. I’ll save most of the stories for later, for whatever this project eventually becomes.

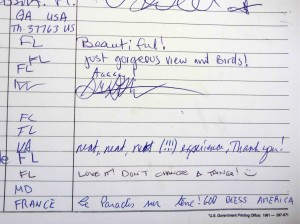

But I’ll share a few of the comments I found from other visitors in a register at the Garden Key dock.

“Keep it up for my grandchildren,” wrote someone from California.

“Thomas Jefferson would be proud,” wrote someone from New York.

“Blissed out,” wrote someone from Kentucky.

And then there was one from Clement S. Barillet of Bordeaux, France. Or at least I think that was the name. I couldn’t quite make out the handwriting. And part of his message I had to translate later.

And then there was one from Clement S. Barillet of Bordeaux, France. Or at least I think that was the name. I couldn’t quite make out the handwriting. And part of his message I had to translate later.

Le Paradis sur terre! GOD BLESS AMERICA

Here was a visitor from a place in France renowned for its wine, declaring this — a place that still doesn’t even have fresh water — to be “heaven on earth.”

– – –

(A few photos from the trip. With a disclaimer. My waterproof camera turned out to be not-so-waterproof. So I had to resort to a combination of old and new media. A disposable, film camera and my iPad. That’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it.)

Next stop: Yellowstone, the world’s first national park, and a different question for the NPS centennial and beyond: What is a national park?

Leave a reply

Fields marked with * are required

4 Comments

09 June 12 at 4:54pm

1

Do you think in 100 years anyone will be interested in visiting the Duval County Court House (assuming it is still standing)? I'm looking forward to reading about your Yellowstone visit - my personal favorite in the Park System.

20 June 12 at 6:55pm

2

Yellowstone! That is my favorite of all the parks I have visited. I would love to go back there someday. Keep us posted on your adventures out west and be sure and share some pics. Happy Trails... Nick

23 June 12 at 2:43pm

3

I can only imagine how beautiful the moon must have looked. What a beautiful place. I plan on visiting with my kids and hopefully grandkids. I am very eager to hear about Yellowstone as well. Wonderful writing my friend!

24 July 12 at 1:14am

4

Thanks. Sunrises, sunsets and Super Moons in the Dry Tortugas were tough to top. But Yellowstone did.