After the earthquake: a place of hope, fear and — most of all — perspective

By MARK WOODS, The Florida Times-Union

MILOT, Haiti — On the way to Haiti, the volunteers on CRUDEM medical teams often spend a night at a Red Carpet Inn in Fort Lauderdale.

The running joke is that it’s a one-star motel on the way down and a five-star hotel on the way back.

That’s what spending a week in Haiti does to you.

When you come home, nothing has changed and everything is different.

The people from Jacksonville who have been making this trip for years, volunteering at a hospital in a small town in northern Haiti, say this was true before the earthquake. But that sensation has been intensified ever since the morning of Jan. 12, when the fruit started to fall from the trees and the roads began to wobble like jelly.

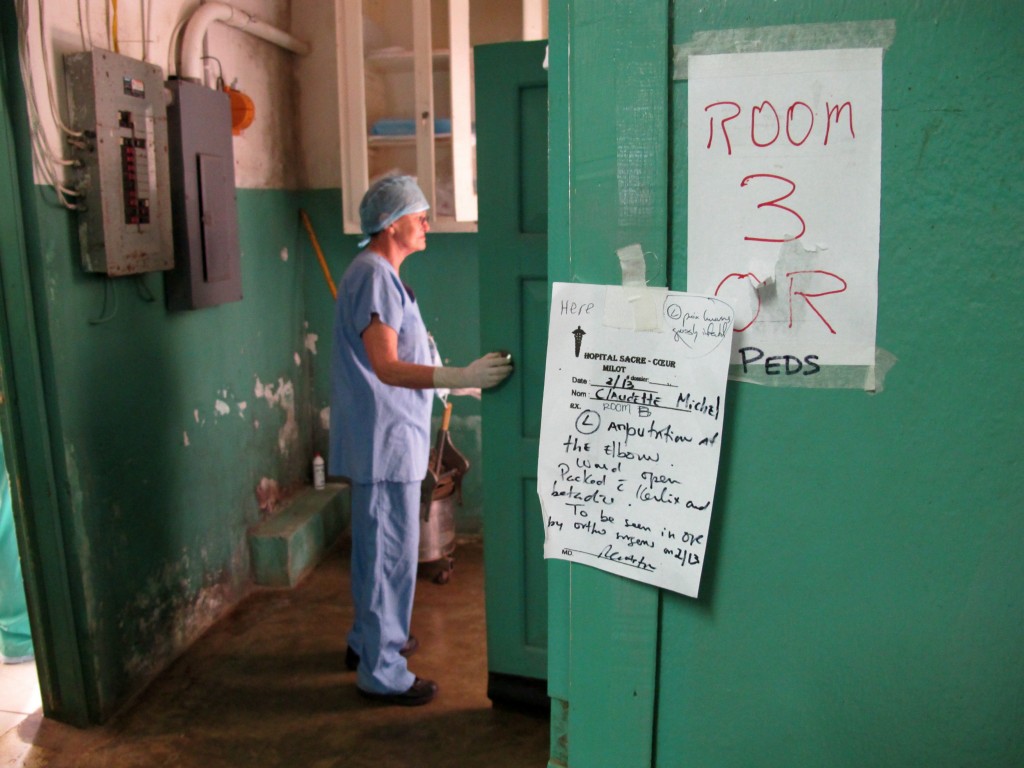

While much of the country collapsed, Hopital Sacre Coeur in Milot emerged relatively unscathed, almost instantly going from a hospital with 73 beds to one with helicopters landing on a nearby soccer field and M*A*S*H-like tents filling with hundreds of earthquake victims.

John Lovejoy Jr., a retired orthopedic surgeon from Jacksonville, led a hastily assembled trip to Milot days after the earthquake. And he returned in mid-February, leading a 22-person orthopedic team on a trip that had been scheduled for months.

At the end of a week that was simultaneously exhausting and exhilarating, Ortho Team No. 7 gathered for a nightly meeting with several other teams representing the U.S.-based CRUDEM Foundation (Center for the Rural Development of Milot). And after running down the clinical details of the day, they tried to put their experience into words. Or, to be more accurate, a single word.

It was the suggestion of Sister Marilee, one of three Catholic nuns living on the CRUDEM grounds. Instead of closing by saying a prayer, she asked that people throw out a single word to sum up what was on their minds. That, she said, would be their prayer.

“Sadness,” someone began.

One by one, words came from all around the room.

Home, support, humility, faith, love, hope, resilience, peace, courage, admiration, family, friendship, sorrow, dignity, unity, grace, exhaustion.

There was laughter, a pause, then more words.

The words piled up, each one connected by a common, unspoken word that hits you the second the small plane’s wheels touch down in Fort Lauderdale, and keeps hitting you at every turn.

Perspective.

“When I got home, I realized I didn’t necessarily miss some of the trappings of Western life,” said Bisi Ajala, a pediatric anesthesiologist at Shands Jacksonville. “I had not watched TV for an entire week. I didn’t have my cell phone. I barely had Internet access, and I had worked like a dog for the entire week. But I was happy.”

Going to Haiti changes the way you look at everything, from the roads you drive on to the food on your plate. It makes you appreciate what you have. But it’s more complex than that simple cliche.

It also makes you think about what the Haitians, some of the poorest people on earth, have.

RESILIENCY

Everyone on the team came home with stories about resiliency. The baby found alive under the nine bodies. The children in the pediatric ward. The old lady who has gone through a lifetime of Biblical-like calamities and somehow still has faith in God and humanity.

For David Balanky, it was a double amputee in Tent 3.

Balanky and his wife, Pat, have been making these trips for years. And even under normal times, if there is such a thing in Haiti, they leave impressed by the way the Haitian people endure adversity. And this time?

“Under these terrible, terrible conditions – crowding, living in tents that were leaking, food shortages, terrible wounds all around them – the people still had a ready smile,” Balanky said.

Especially Joseph.

Nineteen days after the earthquake, 26-year-old Joseph Edelyn had both his legs amputated above the knee. And while, yes, your eyes initially are drawn to the bandages on the stumps where his legs used to be, you end up focusing on his boyish face.

“He had a smile that lit up the tent,” Balanky said. “He was like a beacon over there.”

Balanky built a trapeze for him, so he could pull himself up in bed. And each day, he ended up stopping by to check on him. One day, through a translator, Joseph told his story.

He had been on a street in Port-au-Prince when the earthquake hit. One wall fell on top of him, then another. He spent two days under the rubble. It was dark.

“I do not know if it is day, or if it is night,” he said.

He said this matter-of-factly. And he calmly described how he was rescued from the rubble. Not that we know what he said. His translator, a middle-aged Haitian man, started to explain, then broke down, covering his face, sobbing.

The translator was not hurt in the earthquake. But he was affected. Everyone there was.

COMMUNITY

The residents of Milot are poor by pretty much any standard. Yet when a steady stream of earthquake victims began arriving in their small town, they started cooking for them, clothing them, singing to them.

And inside the tents, families took care of all the duties that in the United States would be handled by hospital staff. Changing dressings, serving meals, emptying bedpans. If someone didn’t have family there, a neighbor in the tent helped out.

When the American volunteers returned home, this is something they kept talking about. How the Haitians helped each other. How little they complained while doing it. How they were so upbeat that sometimes you forgot what they had been through.

FEAR

There were, of course, moments when the reminders came flooding back.

Jeff Hills, a physical therapist from Jacksonville, tells a story about the time a doctor decided it was time for a trunk cast to come off one woman. When they started cutting, the woman started screaming. They tried to assure her that the saw would only cut the cast, not her. They couldn’t figure out why she was getting so upset. Then, with the help of a translator, she explained.

The vibration reminded her of the earthquake.

UNCERTAINTY

She was swaddled in a white blanket and taken to the nearby soccer field, which became a busy landing pad. As the sound of a helicopter filled the air, a nurse gently rocked Richnulda Pierre.

The baby was flown to the USNS Comfort, returning a few days later along with a bad haircut and the neurosurgeon who gladly took full responsibility for it. A paramedic carried her to her awaiting mother.

With the baby in her arms, the mother stood smiling.

When the earthquake hit, she thought she had lost her home and her family. Three days later, they started pulling the bodies out of the rubble. Her husband was dead. Her 5-year-old son was dead. Her baby was dead. Or so she was told.

She said she wanted to hold her child. And when she did, she saw a hint of life.

They ended up in Milot. The medical treatment was good, so good that Pierre was about to be discharged from the crowded pediatric ward, making room for another child.

After answering questions about her story, she asked the translator if she could say something else. She said she was grateful for all that had been done. But she also was scared. She had no husband, no home, no job. She wanted to work. But where? What was she going to do tomorrow?

This isn’t just her question. It is the question of hundreds of thousands of Haitians.

HUMOR

One day, a group came through the tents, handing out care packages.

One man, a double amputee, excitedly opened his bag and pulled out … a pair of socks.

You could see the disappointment on his face. Socks? For a man with no feet? But whatever sadness he felt was fleeting, lasting only until the man on the cot next to him opened his bag and pulled out … women’s underwear.

They all burst into laughter.

When Joe Sindone, a podiatrist from Shands Jacksonville, retold this story, he said he had prepared himself to find a lot of things on his first trip to Haiti. The poverty, the bad roads, the earthquake injuries. But he hadn’t expected to go there, especially now, and find humor. And yet at every turn, in every tent, amid the pain and suffering, there were smiles and laughter.

HOPE

One of the nurses from another CRUDEM team walked with a limp. Lovejoy, the leader of the Jacksonville team, decided to ask her what had happened.

She explained that when she was 12 years old she was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a cancerous bone tumor. She had a 10 percent chance of survival. They replaced the bone with a cadaver bone. It broke several times. And when she was in college, after the fifth or sixth break, she decided to go ahead and have the leg amputated.

That was 23 years ago. She’s married, has three children and is a nurse. And here she was in Haiti, a land now full of amputees.

With this in mind, Lovejoy took her to the tents. In most cases, the sight alone had a profound impact. But there was one woman who said, “I’ve lost my leg and I’ll never dance again.”

Lovejoy grabbed the nurse and they started dancing around the room. The other patients started singing.

When they were done, an elderly woman grabbed hold of the nurse’s hand and wouldn’t let go. They called over a translator. And she relayed the woman’s message: “I was ready to give up. Now I’m ready to live.”

In the span of one week, there was a lot of this. Maybe not quite this dramatic. But slowly, and surely, you could see it happening.

More than 200,000 people died in the earthquake.

Yet the tents were full of life.

COMFORT

It was the team’s final night in Milot, the meeting where Sister Marilee asked them all to come up with a word for their experience. Nobody said “death.” But it is an omnipresent part of life in Haiti.

Several times during the week, the sound of “Auld Lang Syne” wafted through the muggy air as a funeral procession headed down the street. And when some members of the team stopped in the cemetery next to the hospital, they found workers digging up remains, creating a vacancy. That’s how it works there, they were told. You only stay in the ground for two years, then it’s someone else’s turn.

And at this final meeting, William Guyol, a doctor from St. Louis who is on the CRUDEM board, told a story about a 32-year-old mother of three who was dying of heart failure.

A doctor wanted to have her transferred to the USNS Comfort for an infusion of medicine. It wouldn’t prevent death, only delay it. Guyol tells the doctor he is sorry, but he cannot ask the Comfort to take her.

At 1:30 that morning, one of the Haitians went looking for the doctor, knowing he would want to be by the woman’s side. Guyol wandered through the nooks and crannies where dozens of volunteers were sleeping. Unable to find the doctor, he eventually decides to go to the woman himself. Jeannie, a paramedic, volunteers to go, too.

The woman looks Jeannie in the eyes and asks if she is dying.

“You are very sick,” Jeanie responds.

The woman understands.

They try to make her comfortable. Pillows for her head, morphine for her pain.

The paramedic decides to spend the night in the tent. As Guyol gets up to leave, Jeannie says something to him, something that makes his voice crack as he tries to repeat it to the volunteers gathered for the meeting.

“She said, ‘She wiped away my tears and that’s not fair,’ ” he says.

He pauses and the room is silent. Some of the volunteers are wiping their eyes. Some are nodding their heads.

They can relate. Maybe it didn’t happen as literally for them. But they went to Haiti and when they become overwhelmed, when they broke down, the survivors of an earthquake wiped away their tears.

And that wasn’t fair.

mark.woods@jacksonville.com, (904) 359-4212

Photo gallery: See the photos from Milot

Leave a reply

Fields marked with * are required