(Published in The Florida Times-Union, Dec. 25, 2005)

The Times-Union

To start to understand what happened last Christmas — how a Catholic priest from Jacksonville ended up standing in an eighth-floor lookout in Fallujah, Iraq, singing Oh Holy Night with a Marine, tears streaming down both of their faces — first you have to hear the other stories about the tears.

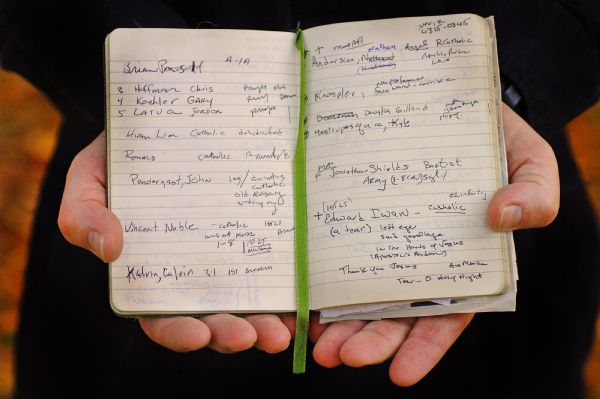

They are all right there in a little green notepad that the Rev. Ron Camarda is flipping through, looking for a name.

When the Navy reservist chaplain left St. Patrick Catholic Church in Jacksonville last year — reluctantly heading to Iraq to serve with the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force and the Bravo Surgical Company — the notepad was new, its binding stiff, its pages empty.

Now the notepad is held together with heavy tape and the pages are full. There are some notes. But mostly it’s just names.

The Rev. Ron Camarda of Jacksonville served as a military chaplain in Fallujah, Iraq, giving last rites to dying soldiers. Back in Jacksonville, he admits he never wanted to go to Iraq. But once there, he realized why he had been sent.

Father Ron, 46, spent nearly seven months in Iraq. He was there during the Battle of Fallujah, the only Catholic priest in a city with an estimated 10,000 troops.

He kept the notepad with him at all times, tucked in a pocket on the right shoulder of his uniform. In a pocket on the other shoulder, he kept the Holy Eucharist.

Each time he ministered to someone, he wrote down that person’s name.

There are more than 2,000 names in the notepad. About 1,500 represent troops who were wounded.

Eighty-one have a cross next to them.

These are the “angels,” the troops he received after they died — or, in the case of 12 of them, as they died.

In his notepad, at the end of each day, there is an updated death toll. These aren’t just numbers. For him, each of these days and each of these names represents a story, much of which he often learned later.

Sitting in an office at Resurrection Catholic Church in Arlington, his temporary home for the past few months, Father Ron finds the page he was looking for.

He points to a name, one that tells the story of the day he stopped questioning why he was in Iraq.

Edward Iwan

(a tear)

It was Nov. 12, 2004. Although the Battle of Fallujah was just beginning, his notepad already included several pages of names.

He didn’t want to be there. He readily admits that.

When he was notified that he had been involuntarily mobilized, he had tried to come up with every reason why he should not be going. He was too old. He was a reservist, a lieutenant commander who had been passed over for promotion. There was a shortage of priests in his diocese. His schoolchildren would be devastated.

He went to the chapel at St. Patrick and talked to God. Even asked him to send someone else.

No such luck. God agreed with the Navy. He was supposed to go.

Iwan

Still, on that day in November, he found himself asking, “Why?” He was tired. He hadn’t taken a shower in four days. All he wanted was a good night’s sleep and, as he said later, to “blow some of this death out of my nostrils.”

At 5:30 a.m., a Marine woke him.

“Padre,” he said, “we have another one.”

He headed to Mortuary Affairs. There was a soldier on the table, young and handsome, but already dead. Father Ron said a prayer and sang a hymn. Then he headed for the showers.

He was standing in front of the mirror, putting shaving cream on his face, when the commanding officer walked in. They needed him. They were losing another one.

He knew that he should leave right away. But he didn’t. Instead, he took his razor and began to shave, slowly, carefully.

“I took my time, not really feeling guilty,” he said last week, choking up a bit, then sighing. “But if I hadn’t taken my time, the rest of this story wouldn’t have happened.”

That delay meant that when he made it to Bravo Surgical, he got caught in the middle of a chaotic scene in a hallway and ultimately was pushed into a place he had never been before: the operating room.

He helped lift a soldier onto a table. He remembers that he had red hair, some tattoos and a gaping hole in his stomach.

The soldier’s Bradley Fighting Vehicle had been struck by a rocket-propelled grenade. The doctors pulled a long, cylindrical piece of metal out of his stomach. They cut open his chest. There was frenetic activity, with a surgeon barking out instructions for the chaplain, asking him to move a light, to hold a bag of plasma and then, finally, to take over.

“We can’t do anything,” the doctor said, leaving the room. “It’s up to you.”

Father Ron stood there, looking at the soldier, trying to figure out what to do, what to say.

“Edward, you’re dying,” he said. “Your dog tag says you’re Catholic. So I’m going to anoint you and forgive your sins.”

He said a prayer. He caressed the soldier’s head and hair. And then, unsure of what else he could do, he began to sing.

Never mind that Christmas was still six weeks away, he sang the same song that he sang to his mother when she was dying.

Oh Holy Night.

The stars are brightly shining.

It is the night of our dear savior’s birth.

He wasn’t even sure if the soldier could hear him. Then, as he sang “a weary world rejoices,” he noticed something.

A tear.

A single tear rolled out of the soldier’s left eye, traveling an inch or two down his cheek before stopping.

The chaplain stared at it.

He would see many tears shed in the desert. But this one tear would stick with him.

When he finished singing, he says, God tapped him on the shoulder, telling him he needed to say something else. At first, he resisted. He couldn’t say that, he thought. But if he didn’t, who would?

So he leaned over.

“Edward,” he said, “I love you.”

Then he kissed the soldier’s forehead. And Edward was gone.

Army 1st Lt. Edward D. Iwan was 28 years old. He grew up on a farm in Nebraska, the oldest of four children. He joined the Army after graduating from high school, served three years, got a degree from the University of Nebraska, then returned to the Army as a commissioned officer.

He did it, his mother told The Associated Press after he died, because he “felt there were people in need.”

He was an optimist. When he got to Iraq, he asked his parents to send seeds. He wanted to see if he could grow a garden in the desert, in the middle of a war zone.

Father Ron didn’t know any of this.

He didn’t know much about any of the 81 names until later, when the Battle of Fallujah ended and he had a chance to go online and start reading Web sites devoted to troops killed in Iraq, or stories in their hometown papers.

As he tried to comfort them during their final minutes of life, sometimes he didn’t know their faith.

Sometimes he wasn’t even sure about their name.

There was this one Marine. He was Catholic. Father Ron knew that much because he had his dog tag tattooed on his body. Name, Social Security number, faith.

Well, not his full name.

S.E. Kielion.

Father Ron had just wearily plopped down on a seat in the chow hall, sliced off a tiny piece of lamb and stuck it in his mouth when he felt a tap on his shoulder.

“Padre, we have another one. Sniper attack. He’s dying.”

He put on his helmet and flak jacket, hopped into a waiting ambulance and rushed to the medical center.

When he ran into the room, he saw a gunnery sergeant holding a Marine’s hand, and the people standing around the gravely wounded man, crying. The commanding officer. The doctor. The nurses.

When Father Ron said a prayer, he wished he could use S.E. Kielion’s first name.

What was it? Steve? Sam? Scott? He didn’t know.

He just knew that the young Marine was dying, a violent, yet peaceful death, if that’s possible. He remembers putting a thumb on his bloody forehead, a hand on his chest. He remembers looking around and seeing all the tears — hearing all the tears — and thinking of a saying he learned while in Haiti.

If a mosquito piddles in the ocean, the water rises.

They were in the middle of the desert, but the water was rising, one tear at a time.

He wrote another name in his book. Or as much as he knew of that name.

The “S” stood for Shane.

Marine Lance Cpl. Shane E. Kielion died Nov. 15, 2004. He was 23. He was from Omaha, Neb., a former high school quarterback who wore uniform No. 1 and helped take a team that had lost 11 consecutive games to the playoffs. He had married his high school sweetheart, April.

Kielion

While Shane was lying on a surgical bed in Iraq, April was in labor in a hospital in Omaha.

The newspaper stories said April Kielion gave birth the same day her husband died.

Father Ron thinks it was the same hour.

He believes that as S.E. Kielion was taking his last breaths, as a small room in Iraq filled with the sobs of grown-ups, on the other side of the world a baby was taking its first breath, letting out its first cry.

A baby boy.

Shane E. Kielion Jr.

Every weekend, Father Ron left the base and went into the city.

He didn’t carry a weapon. He traveled with Patrick, his bodyguard, who carried an M-16. On an average Sunday, he celebrated Mass nine times. He kept his homilies short.

As he spoke, he thought about Mother Teresa, telling himself to celebrate every Mass as if it were his first Mass, his only Mass, his last Mass.

And in the city of Fallujah, the latter certainly was a possibility.

Lt. Cmdr. Mike Euwema, a Navy doctor from Jacksonville, arrived near the end of Father Ron’s time there and was his roommate for a few weeks.

“Our base was relatively safe,” Euwema said, describing a place surrounded by walls. “… But Father Ron would go out with his RP [bodyguard] and do Masses in the forward operating bases where there were no walls. … He’d risk his life to give Mass.”

Father Ron downplays any talk of bravery, joking about how — despite his time in the Merchant Marine and Coast Guard — he was hardly a model of Acta non Verba (actions not words) or Semper Paratus (always prepared). He does say that perhaps it was fitting that, as a chaplain, he ended up pitching his tent among the Marines.

Semper Fidelis.

Always faithful.

This, he says, was faith at its rawest, ministry to the “poorest of the poor,” the wounded who were down to their last breath.

“He’d always materialize out of thin air, and be standing at the head of the bed, saying something quietly,” Euwema said. “And if he didn’t know what to say, he’d sing.”

Dec. 25, 2004.

It wasn’t a white Christmas in Fallujah.

It was a wet one, a brown one.

It rained, and the dirt turned to mud, only making Father Ron’s homily for that day seem even more far-fetched: This has to be your best Christmas ever.

There wasn’t peace on Earth, but there was silence in Fallujah. In November, one of the deadliest months of the war, there had been little time to think, to reflect. Then, all of a sudden, it seemed like there was nothing but time.

Father Ron had gone on the Internet and learned about the names in his notepad. He thought not only about them, but about the people whose names he didn’t know. One day he saw the bodies of about 400 Iraqi civilians, people who wouldn’t, or couldn’t, get out of the city before the battle.

He began to write, about the names, about himself, about the war. He still had his doubts about why we went there. But he no longer was questioning why he was there. He had a job to do. And now that he wasn’t doing it, he was bored. He missed the adrenaline rush that came with the angels. And he didn’t like learning this about himself.

You have to make this the best Christmas ever, he preached. To others and to himself.

Not everyone could make it to Mass in the formal setting. So he spent much of the day making house calls. Or mess hall calls. Or, that night, a lookout call.

He was told there was a Catholic Marine who hadn’t been able to receive Communion. So he went to where the Marine was, on the eighth floor of a grimy building in the middle of Fallujah.

As he climbed the stairs, the smell of the city overwhelmed him.

“You could smell death,” he said.

He got to the lookout and found four battle-hardened Marines. He asked which one was the Catholic. It was the one who was smoking a cigarette.

He took him aside and gave him an abbreviated version of the homily, repeating the message that this had to be his best Christmas ever.

The Marine looked at him like he was crazy.

But when he prepared to receive Communion, he reverently held out his hands. They were filthy. Father Ron remembers that. But more than that, he remembers the Marine held them there, as if he was making a throne for the Eucharist. And he remembers asking the Marine if he would sing with him.

On Christmas night, in a desert in the Middle East, they began to sing the same song he sang to his mother when she was dying, the same song he sang to Edward when he was dying.

Oh Holy Night.

The stars are brightly shining.

It is the night of our dear savior’s birth.

At first, the chaplain led the singing. But as they went along, the Marine began to sing louder and louder, until he was belting the carol out at the top of his lungs.

OH NIGHT DIVINE!

OH NIGHT WHEN CHRIST WAS BORN

His buddies in the nearby room could hear him. The troops on the ground floor could hear him. Father Ron wouldn’t be surprised if he learned one day that people on the other side of Fallujah heard him.

When they finished, the Marine opened one eye and impishly looked over at the priest.

“Padre,” he said, “this is the best Christmas ever.”

There were tears running down their faces.

More water rising in the desert.

Only this time it wasn’t because they were mourning a death. This time they were celebrating a birth. Celebrating it in a way you don’t soon forget.

Not one year later.

Probably not ever.

mark.woodsjacksonville.com, (904) 359-4212

Leave a reply

Fields marked with * are required